. My Dad’s Side The “Finnegan” (remember, that’s my pen name) family history in America is varied and fun to trace. I will try to tell it as a story, rather than burden you with dates, lists and dry facts.

I grew up near my Dad’s family, in Chicago, so I am much more familiar with them than with my Mom's family. The Roneys of my mother lived in and near Washington, DC, and we saw them only occasionally.

Before we tackle the scholarly aspects of the tale, please understand that I raised the subject of family history – “Where did you come from, Grandma?” – many, many times in my youth. My questions were humored, but not answered. “Why do you want to know?” was the usual response, and I now understand why. The roles of kids and adults were very precisely defined in the 1950’s. The adult was the teacher, and the enforcer. The child was the student, and the one who obeyed. Entertaining a kid’s questions exposed the adult to (1) the work of remembering, (2) potential – nay, certain – contradiction by other nearby relatives who saw the truth by their own lights, and (3) having to say, “I don’t know” at certain points. Since any such outcome would transfer power from adult to child, and since there was no obvious way to win (important to Finnegan family discussions, which always devolved into arguments), it was safer to refuse to answer. Thus, my ignorance.

I have gleaned some facts, and I have discovered others through research over the years. So, here is the story.

My great grandfather on my father’s side was John. He was born in 1856 in Tipperary County, Ireland. Many, many families with our last name lived in Tipperary, and many Tipperary “Finnegans” emigrated to Chicago from 1850 to 1900. Family tradition that he came from Cork is partially accurate: while it was not his home, many Irish emigrants passed through Cork on the way to its port, Cobh (pronounced “cove”), where the ship to America waited for them. He emigrated in 1888, at age 32.

The facts of his move from Ireland to the United States are curious. He was older than average. He was single. He was born after the Potato Famine (1845-1850), and he grew up during the greatest Irish migration in history, so none of those factors alone propelled him to America.

Since he arrived just before Ellis Island got into processing immigrants (1892-1924), we cannot easily find his records of birth, parents and so forth. A person might stay behind in Ireland while his friends and family went to Chicago if, for example, he had to care for an elderly parent until he or she died. He might be single because he found no fiancé, or because his betrothed went on ahead to America. In his time waiting in Ireland, he learned a trade as a butcher.

John's (or “Jack’s”) exact Irish history and specific motivation to come to America are not yet known. But the fact of severe Irish poverty at the hands of the English occupiers, the fact that the English prevented Irish Catholics from owning land in their own country, the fact that the English rented Irish land and homes to Protestants from England and Scotland, and the fact that 2,000,000 Irish had left for America with good results – these facts had the same effect on John as they had on his predecessors. In 1888, he got on a ship, and sailed for America.

He did not spend any time in New York. The Irish in America had finally gained acceptance by hard work in building railroads, by taking jobs as policemen, teamsters and manual laborers of all types, and particularly by the way they fought on both sides of the Civil War. John was welcomed, and he went directly to Chicago where his people waited for him.

Chicago’s population in 1890 was 1,700,000, including 600,000 people who were foreign born. Of these, 74,000 were born in Ireland.

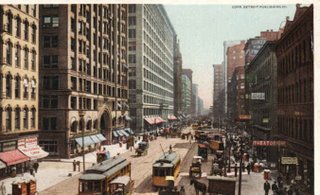

Chicago, 1900

When John got to Chicago, he settled on the southwest side of the city, in a district of skilled immigrants known as “Back of the Yards”. The neighborhood extended from 39th to 55th Streets between Halsted and Leavitt Street, just south and west of the Union Stock Yard and meat packing plants. It was a giant sprawl that was the largest livestock and meatpacking center in the country until the 1950s.

Adams Street, East of Clark, 1888

The concentration of railroads in the 1850’s, the establishment of the Union Stock Yard in 1865, and the perfection of the refrigerated boxcar by 1880 led to a giant expansion of meatpacking in the neighborhood. It was settled by skilled Irish and German butchers. Here in 1889, developer Samuel Gross built one of his earliest subdivisions of cheap workingmen's cottages. By the turn of the century the area was transformed into a series of Slavic enclaves dominated by Poles, Lithuanians, Slovaks, and Czechs, with most communities organized around ethnic parishes serving as social and cultural as well as spiritual focal points for residents' lives.

Chicago, 1900

Chicago, 1900

Immortalized for its pollution, squalor, and poverty in Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle (1906), Back of the Yards was actually a collection of very vibrant and cohesive working-class communities. Wages were low for unskilled workers, but butchers were at the top of the scale.

John took his time leaving Ireland, for one reason or another, until he was known as middle aged. In Chicago, he picked up the pace. In the 12 years between his arrival in 1888 and the census of 1900, John found and married his wife, got a home, got a job, and fathered six children. John’s and Kate’s accomplishments are impressive.

John got together with Catherine just as soon as he got to Chicago. She was ten years younger than he, born in 1865 in Ireland. She arrived in the United States in 1883, and we know her from the census as Catherine M. I think that John and Kate (as she was known) knew each other in Ireland, because they married almost as soon as John unpacked his suitcase. Their oldest child, Mary, was 12 years old in 1900.

Mary was born in 1889, Edward in 1890, Martin in 1892, Patrick in 1894, Richard in 1896 and James in 1899. James was christened James Martin, and he became my Grandfather. Not right away; later.

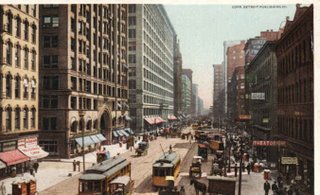

Chicago, Dearborn & Randolph, 1909

Chicago, Dearborn & Randolph, 1909

Chicago in 1900 was a booming city. The downtown was virtually new, after rebuilding from the 1871 Chicago fire. It had a 2,300 man police force. The police department fed and housed over 170,000 homeless people inside its stations in that year. There were 62 licensed hospitals in 1896, and most were new and modern.

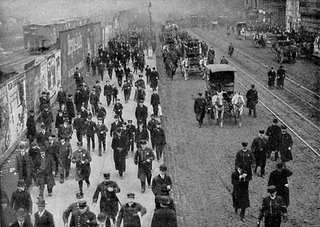

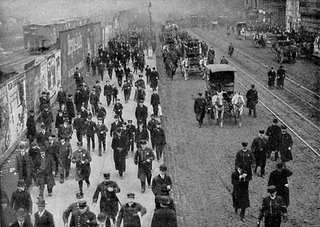

Chicago Police, 1902

Chicago Police, 1902

The health of Chicagoans was good in 1900. Infant mortality was decreasing, and people were living longer. For the first time, deaths were caused more frequently by degenerative diseases such as cancer and old age than by epidemics, accidents and infection. Sanitation was improving, with the Sanitary and Barge Canal taking wastes to the Mississippi and water treatment plants installed in Lake Michigan for drinking water. Indoor toilets and baths were the current rage, though John and Catherine’s family were not rich enough for those conveniences. Public baths were plentiful for a fee, and there was always the large galvanized wash tub for Saturday night.

In 1900, the family lived at 5238 May Street, on Chicago’s south side. It was likely a tenement building, and with a large young family, they may have had the first or second floor. Thirty years before, the Great Fire had started only 30 blocks north, sweeping north and east.

Not My Family, But It Could Have Been

Not My Family, But It Could Have Been

The address is half a mile south of the Union Stockyards. For comparison, Disneyland in California now occupies about 300 acres, including hotels; the Union Stockyards was a 475 acre complex, a city within the city. The poet Carl Sandburg called Chicago “Hog Butcher to the World” because of the stockyards.

About 50,000 people worked in the area, in the meat business. The headquarters offices of the big packing companies, like Armour and Swift, with hundreds of white collar jobs, were next door to the slaughter and processing buildings. The plants themselves were connected in a pattern in which the hogs, cattle and sheep were slaughtered and sorted by grades and cuts of meat. They had assembly lines which Henry Ford later copied for his automobiles. One would more accurately call them "disassembly lines". Hundreds of by products like animal feeds, tennis racquet strings and pharmaceuticals were made on the spot.

My great-grandfather John worked in the stockyard as a butcher. His job meant that during the desperate times of the Depression in the 1920’s, John was still able to put fresh meat on the table for his family.

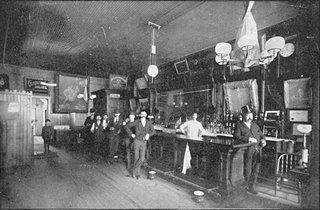

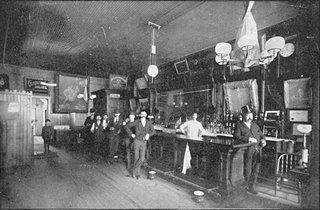

Chicago Saloon, 1900

Chicago Saloon, 1900

The records of the Chicago Historical Society report that the unpleasant smell of the stockyards permeated the adjoining neighborhoods, spread by the humid breezes for many miles. But, the working people said that the smell meant work. There were as yet no buses, trains or cars. Electric Trolleys were limited to the downtown area. Commuting to work was mostly by foot, so workers had to live near their work. For these reasons, the family tolerated the unpleasant environment and lived near the stockyard because that’s where John worked. And perhaps some of his kids, too.

In the 1920 census, we learn that the family has moved a couple of blocks away, to 5427 Racine Avenue. By today’s map, the new place is one block west and two blocks south of the May Street home. Then, and now, Racine is a wider street with more shopping and better homes and apartment buildings. It is also further away from the stockyards. Directly across the street is Sherman Park.

John and Kate Move Up In The World

John and Kate Move Up In The World

Sherman Park was one of ten remarkable Chicago parks which opened to the public in 1905. The city's population had grown from 300,000 in 1870 to 2 million by 1905. The noisy, overcrowded immigrant neighborhoods were far away from the existing parks. South Park Commission Superintendent J. Frank Foster envisioned a new type of park that would provide social services such as public baths as well as breathing spaces to these areas.

Sherman Park Field House, 1905

Sherman Park Field House, 1905

At 60 acres, Sherman Park (named for the founder of the Union Stock Yards) was one of the largest of the parks. The architects transformed the low, wet site into a beautiful landscape. A meandering waterway surrounded an island of ballfields. The classically-designed architecture, located at the north end of the park, includes the fieldhouse, the gym and locker buildings united by trellis-like structures called pergolas.

Sherman Park became John and Kate’s new front yard.

The move shows that John and Kate are prospering. By 1920, Mary, 32, and Patrick, 26, have moved out, and there are two new people in the household: Eugene J. born in 1902, and Catherine M., a granddaughter, born in 1914. John is now 63, Kate is 56, and they own an apartment house. From immigrants 32 years before, they are now landlords.

State Street, 1905 – One Year After My Grandmother Was Born

State Street, 1905 – One Year After My Grandmother Was Born

(Disregard that whirling, twirling sound you hear coming from her grave…)

James enlisted in the Navy just as World War I ended and he turned 17. He was a Yeoman, a clerk in the office of the Captain of a battleship. His battle station was on the bridge, as a messenger for the Captain and as an assistant helmsman. By 1921 he had left the Navy, and met, courted and married my grandmother, Evelyn Letourneau. I was told that they lived for a time with Jim’s parents, and then moved to their first apartment on Vincennes Street.

When one searches for the origins of Chicagoans named Letourneau, Quebec dominates the results. That may be the ancestral home for Evelyn and her brothers and sisters: Al (and wife Jeanette, and son Steve who became a California MD), Helen (aka Dolly, and husband Frank Aerts of Pasadena CA), Cele (perhaps a contraction for Celia, and husband Jim Berry, also of California), Bernice (Sullivan and daughter Patsy), and the youngest, Phillip (who added a precocious “x” to the end of Letourneau, wife Helen O’Leary of Boston and son Steve). We do not think that there is a connection between Phil’s wife and the famous lady whose cow started the Great Fire of 1871. But, Helen also did not advertise her ancestry to Chicagoans.

None of my Letourneau relatives spoke French, talked about Canada, or even visited up north. If they were French Canadian, their ancestors came to America generations before. To me, they were our well-to-do Chicago relatives, some of whom had defected to California in the 1940’s.

As their parents had before them, James and Evelyn set to raising a family. Their first born, James Thomas, became my father; he was born in 1921. Next was Helen Jean, 1924; and Richard, 1927. The last was Therese, 1934. In those years, they moved first from Vincennes to 72nd and Wentworth (2 miles). When my parents were married in 1947, they moved in to the Wentworth apartment with my grandparents and Helen, Richard and Therese. I was born first, then my sister Christine. From Wentworth my grandparents, parents and all moved to 69th and Indiana (half a mile), a large house where they had the first floor. It was down the street from the firehouse. I have memories of that house, including the fire engines (“fufagenjines”), and the old men playing cards on the back porch and feeding hot mustard to a little boy (bastards, I called ‘em), and the corner store. Then, in 1951, my mother became pregnant with my brother Jim, so my parents moved to a duplex house, at 9813 South Yates, and my grandparents, Helen and Therese moved to the first floor of 524 West 103rd Place – about 8 miles south of 69th and Indiana. Richard soon married Gloria.

That brings us to the 1950’s – one hundred years of the “Finnegans” in America. I’ll continue the story at that point, soon.